Quaternary Shropshire – The Landscape

The Quaternary Period started 2.6 million years ago and has lasted until the present day (though this is debatable in connection with the concept of the Anthropocene). The Quaternary is divided into two Epochs; the Pleistocene and the Holocene. The Pleistocene is often referred to as the ‘Ice Age’, though this is a bit of a misnomer. There are four recorded glacial advances in Britain’s Pleistocene; the Beestonian (>866ka), the Anglian (478-424ka), the Wolostonian (352-130ka) and the Devensian (115-11.7ka). Being the most recent, the Devensian Glaciation is the best represented in Shropshire, having helped shape the landscape that we see today. Keep reading to see some of the landforms left by this age of ice.

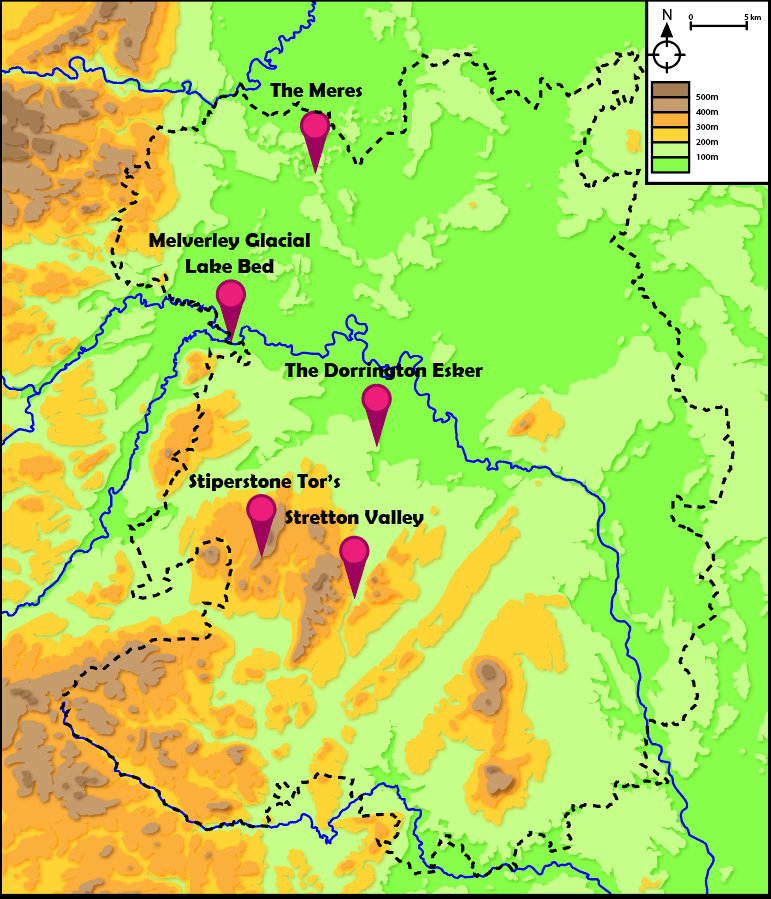

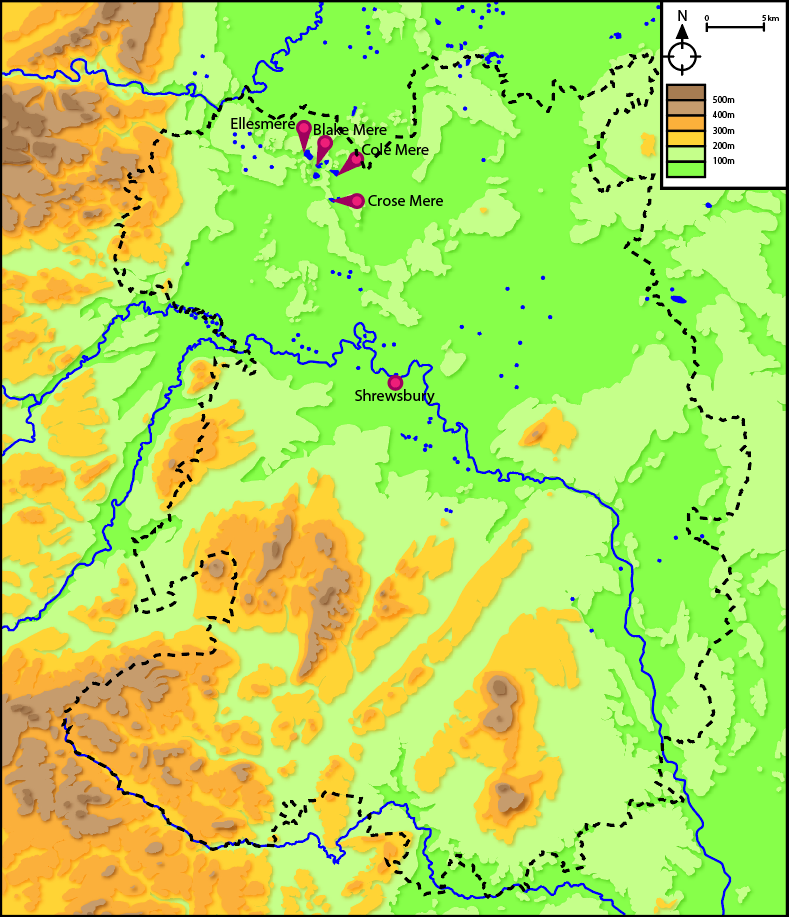

Mosses & Meres

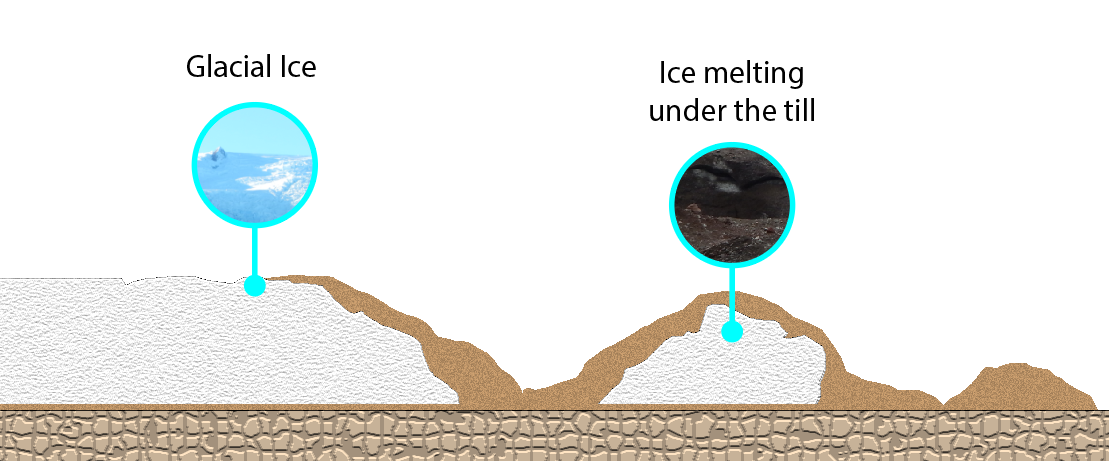

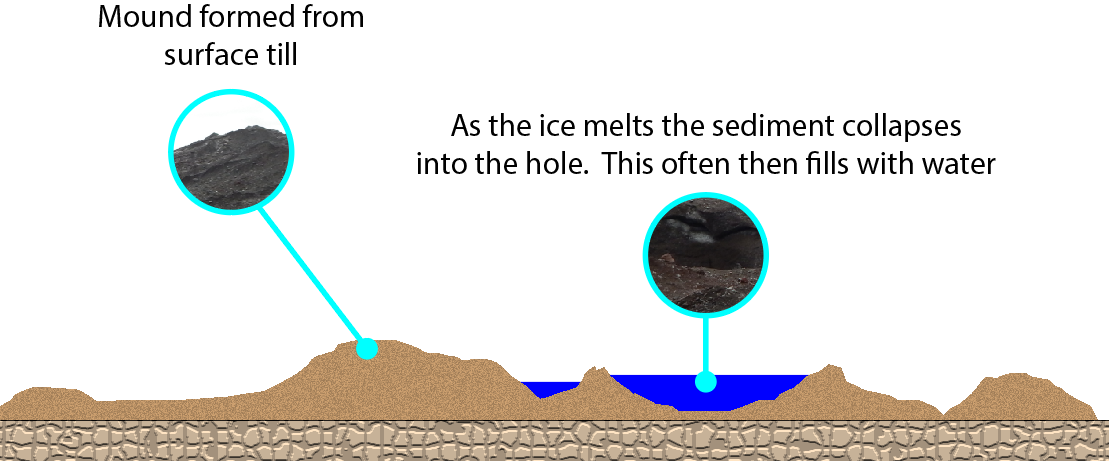

No discussion of Shropshire’s glacial history would be complete without talking about the mosses & meres that are dotted all over the northern half of the county. Many of these are kettle holes, a glacial landform created when chunks of ice break off from a retreating glacier and get covered in sediment. Later this ice melts, leaving a depression behind in the ground that then gets filled in by water. Lakes such as Blake Mere, Cole Mere, Crose Mere and the largest of them all, Ellesmere are all kettle holes; the relics of a dying glacier.

Surface debris left on top of the glacier forms mounds near the kettle holes known as kames. The kettle holes are so prolific that there are dozens of them over Shropshire. Today these lakes are used for recreation, water sources for agriculture and perhaps most importantly of all as nature reserves for wildlife. Many are open to the public where one can take a walk and view the remains of Shropshire’s glacial past.

Lake Beds and Outwash Plains

North Shropshire is mostly a flat plain, the remains of a mixture of glacial moraines, outwash plains, pro-glacial lakes, melt water channels, kettles & kames. Climb a hill such as the Wrekin and you can see the contrast in the landscape between the hilly south and the flat north.

In the very west of Shropshire, near the village of Melverley the rivers Severn and Vyrnwy meet. Some 16,000 years ago this was the meeting point of the glaciers that ran down their respective valleys, and as the ice melted, it created a lake. The wide, flat river valley is all that remains of this lake. At times of heavy rainfall the rivers can still flood on to the plain, temporarily forming a lake once more.

The Dorrington Esker

North of Dorrington is the a low, linear feature in the landscape, now mostly covered in trees. This long mound is an esker; a fluvio-glacial formation that occurs when a meltwater river forms underneath the glacial ice. Like most streams, sediment is deposited along its course, and over time slowly blocks the channel. As the ice melts away these lines of sediment are revealed as long ridges that snake across the landscape. This is the best preserved esker in Shropshire and can be seen from the A49 and Lyth Hill. If you want to visit the esker there is a small lay-by on the road north out of the village of Stapleton, then walk to where the road bends west at the north end of the esker and through the gate. N.B. The road is narrow and there is no footpath so beware of traffic.

The Stretton Valley

The Stretton Valley is part of the Shropshire Hill’s AONB. At one point the valley was the meeting place of two glaciers; one coming off the Welsh & Ice ice sheet to the north, and part of the Onny Valley glacier from the south. Once the ice started to melt and both glaciers retreated towards their respective ends of the valley they left an area of poorly defined moraines, which much of Church Stretton now sits on. This also forms the watershed for the streams running out of the valley.

Although glaciers have helped to shape the Church Stretton Valley, it is not a glacial valley in the strictest sense. It is largely the result of Church Stretton Fault and the Ediacaran hills on either side. The Pleistocene glaciations are just the most recent of erosional episodes in this landscape’s long history.

Nover’s Hill is a small hill attached to the Long Mynd, between Church Stretton and All Stretton. It is made up of the same Ediacaran siliciclastic rock as the rest of the Long Mynd. It does however show an interesting feature; a glacier valley formed on the hill’s western flank. This small, steep-sided valley is the result of ice flowing from the north, and when it hit the side of the hill most of the ice flowed down the main Stretton Valley whilst a small amount made its way around the western side of the hill. The ice then moved southwards eventually rejoining the main glacier just north of Church Stretton. Had it been a little higher up the hill it could almost be called a hanging valley.

Frost Shattered Tors

Atop a ridge of hills known as the Stiperstones one can visit a series of tors. These rocky outcrops rise above the moorland that covers the rest of the hill. Made of quartz rich sandstone from the Ordovician Period (466-478 ma) these rocks have been broken up by frost shattering; a process of erosion that takes place when water seeps into fissures in the rock and then freezes when the temperature drops. As the water freezes it expands, opening these cracks even more. During the Devensian Glaciation the Stiperstone ridge was above the glacial ice, but was subjected to long periods of sub-zero temperatures, and it was during this time that the bulk of the frost shattering took place on these tors.